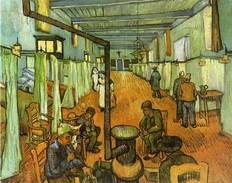

Ward in the Hospital at Arles Vincent van Gogh 1889

Ward in the Hospital at Arles Vincent van Gogh 1889 In the late evening of Friday, February 22, 1878 they glumly sat, side by side, in the waiting area of the Kingston General Hospital, waiting for Dr. Fee. Thomas Albert Hersey (1839 - 1910), carpenter by trade, was feeling faint. His right hand was wrapped in a tea cloth and was bleeding profusely. He did not dare peek through the cloth; he might find a severed thumb. Would he be able to use this hand ever again?

David John Hersey (1846–1900 or so), a truly outstandingly gifted book-keeper, whose injuries were far minor in comparison, was sure he was going to die. He was going to be deformed. Bleeding from the crown of his head, the back of his head, as well as around both eyes, he was convinced he would turn blind. Would he ever be able to read again?

Thomas stiffly and painfully turned to look at his brother. David always dressed like a dandy. Thomas's eyes began at David's crushed-inward bloodied beaver top hat, briefly noted the few cuts around his brother's eyes, and stopped at the blood-streaked silk handmade shirt. This was ripped around both armpits, rain and mud soaked, with the trim collar swinging pathetically by one thread. David's silk blue imperial neck scarf was tied around his head to stop the flow of blood, making him look as if he had the mumps. Glancing down below David's waist, Thomas noted that the suspenders, which had somehow become wrapped around the left leg, were miraculously towing the brown mud-skewed, previously Prussian blue checkered waistcoat. Once perfectly fitted, David’s pinstriped trouser outer seams were split apart; fifteen inches on the left leg and the full length of the right. Thomas could not see the split up the back seam, as they were both seated. Oh dear, it seemed as if David had lost one of his patent leather boots and a sock. David's wool chesterfield overcoat was lying in a soggy heap by his bare foot. Peeking out from beneath the coat, were those two brown rags? No, those had been David’s button-up white gloves. Saved, however, was the cherished gold watch and chain, which he had gripped in his right hand.

"Well," Thomas sighed.

"Yes?" replied David.

"Well, at least we got father off the roof."

Thomas stiffly and painfully turned to look at his brother. David always dressed like a dandy. Thomas's eyes began at David's crushed-inward bloodied beaver top hat, briefly noted the few cuts around his brother's eyes, and stopped at the blood-streaked silk handmade shirt. This was ripped around both armpits, rain and mud soaked, with the trim collar swinging pathetically by one thread. David's silk blue imperial neck scarf was tied around his head to stop the flow of blood, making him look as if he had the mumps. Glancing down below David's waist, Thomas noted that the suspenders, which had somehow become wrapped around the left leg, were miraculously towing the brown mud-skewed, previously Prussian blue checkered waistcoat. Once perfectly fitted, David’s pinstriped trouser outer seams were split apart; fifteen inches on the left leg and the full length of the right. Thomas could not see the split up the back seam, as they were both seated. Oh dear, it seemed as if David had lost one of his patent leather boots and a sock. David's wool chesterfield overcoat was lying in a soggy heap by his bare foot. Peeking out from beneath the coat, were those two brown rags? No, those had been David’s button-up white gloves. Saved, however, was the cherished gold watch and chain, which he had gripped in his right hand.

"Well," Thomas sighed.

"Yes?" replied David.

"Well, at least we got father off the roof."

RSS Feed

RSS Feed