22 Feb 1878 Standing at the foot of the Princess Street bridge, David John Hersey (1846 –1900 or so), an able and very talented book-keeper, was about to face another challenge. It was dark, almost 5:00 P.M. on a stormy Friday. He had been running through the mud soaked streets of |

Kingston, Ontario for near an hour and had suffered several slips and falls, ripping and muddying his clothes. Compelled to check on all various members of The Family, he had left his office early to trek through the rainy city. He had already satisfied himself that his and his sister's residences, which were on relatively high ground, were secure. The structures had not sustained any physical damage. He had, as he had expected, found his wife, Elizabeth Kells Hersey (1845–1931), in a state of panic. She had a great fear of loud thunder storms. After calming down his family, he had made it up Barrie Street to Princess, and had stopped at the brick bridge. Below, Williamsville Valley was in full view. This was low ground where all run-offs headed. And this was where the city had not built adequate infrastructure to compensate for drainage. It was worse than he had anticipated.

The bridge proved to be a disaster. The bricks were slimy, slick, with no traction for footing. David fell forward into a somersault. Having little acrobatic ability, this proved to be a bruising and scraping fall. He rolled from the apex of the bridge to the base of the street, cutting and bashing the front as well as the back of his head. He lay in the mud for several moments, dazed. Soon he realized his French made silk shirt was becoming blood soaked. This put David in a state of fright. He hated blood. He could not feel his injuries, but he knew they surely must be severe. Realizing the blood was originating from the area of his anatomy that should house his hat, he removed his blue silk scarf and tied it around his head, hoping to stop the flow. What was left of the hat had blown into a soggy ditch at the side of the road.

David John gathered his wits; he needed to check on the remainder of The Family. With thunder blaring, rain pouring, and wind at his back he continued east on Princess Street and turned north into the flood on Chatham Street. His brother's home, Thomas Albert's (1839–1910), was three blocks up. Just as he turned off Princess Street a jet of water swept him off his feet and he slid almost ninety feet, as it were, home, the rest of the way to his brother's residence.

He made it up the porch but did not knock. He threw open the door and stood at the threshold for all to see; bloodied shirt, ripped trousers, collar hanging loose, blue neckerchief tied around his head, waistcoat and suspenders falling to his hips; he was a water-monster sight. Lightning struck and his terrifying condition was revealed. His sister-in-law, Elizabeth Evans Hersey (1842–1933), dropped the pail of rain water she was holding, spilling it onto the floor. The six older children froze in their tracks, gaping at him. The younger four, two sets of twins, started bawling.

It took five minutes to calm the twins and gather order.

"Great Heavens, David? What happened to you? Is everything alright in town?"

"Yes, yes, yes, everyone uphill is safe. I came to check on you, Thomas, and Father and Mother."

Clear to Elizabeth was the fact that it was David John who needed to be checked on and given care.

Repeated lightning strikes allowed him a look around the house. He gazed in amazement into the parlor. He was accustomed to Thomas's house being…untidy…perhaps chaotic. After all, there were ten children of all ages running amuck. But this sight was a calamity. Every carpentry tool used by his brother and their father was thrown, willy-nilly, about the room. The piano seemed to be housing the longer saws. Chairs were filled with hammers, compasses, and wrenches of every sort. Another lightning strike revealed a floor piled with miter boxes, clamps, axes, hatchets, every tool imaginable.

Elizabeth tried to explain. "The tool chests were too heavy to carry upstairs so they're bringing everything up one at a time."

This was an especially annoying turn of events. It had been David John, himself, who had carefully decluttered and systematized Thomas's and father's basement workshop. In David's opinion, the two of them had little sense of order. They had needed his expertise. Before David's intervention it had seemed to take the two an inordinate amount of searching through the hodgepodge to find a tool. There were two sets of most items. Decades before, while still a Yankee, father's Uncle Jonathan had purchased father's tools and arranged for his carpentry apprenticeship in Boston. Nostalgia, coupled with father's tendency to resent sharing, had caused some minor squabbles. In order to maintain peace father had solved the problem by graciously purchasing Thomas his own separate set of modern tools. A few of the tools were unique for Thomas, who was left-handed. It was necessary for there to be several sets of scissors. For the same reason, Thomas had made his own tape measures with all numbers and marks reading right-to-left. After David had finished, the basement was a well-ordered work shop; Thomas's tools hung on the north wall and most of father's on the east; every nail, screw, and bolt was sorted by type and size in labeled boxes. It had been an enormous and time consuming undertaking.

William Hersey, the oldest son (1863–1938), appeared up the steps balancing three boxes of nails. These he tossed on the settee and they immediately spilled onto the floor in a mixed mess.

"Is Thomas in the basement?"

A screaming torrent of explicitly non-Methodist language coming from below answered David's question.

"Thomas!!" Elizabeth yelled as they ran down the stairs. The un-Christian epithets became louder and coarser. Near the base of the stairs David gazed on the second scrambled scene of the residence. The floor was covered with three feet of rapid flowing water. An oil lamp sitting on a bench revealed the disaster. All small and loose items were washed up and clinging to the east wall. Most of the benched tools had been removed. Both doors had been broken open by the flood waters and the chairs and stools were hanging for life against the jams. Thomas stood by the south wall, cradling his right arm, bent over in pain. Blood was running heavily from his hand. The culprit, a large crosscut saw, lay underwater at his feet.

William hurried back down the stairs declaring, "Uncle, we are going to have a cave-in!" He was pointing at a small, two inch hole in the plaster of the north wall which was spewing a small fountain of water. The hole was clearly getting larger.

While Elizabeth flew into action to examine Thomas's hand (he was reticent to both let go of his arm and stop swearing) David scanned the premises for a solution to the growing hole.

"We have to stuff it with something," William yelled.

Rags? A hammer? A piece of wood (there was nothing small enough)? A hand-full of nails? His shirt?

Fast action was in need. The hole had grown to a triangular shape of about three inches and was getting larger. David, thinking "triangle, triangle" tore off his right boot and jammed it into the hole, toe first. It held. The Prussian blue mud stained silk stocking dangling over the boot heel made a colorful touch.

At this point Freddie, the youngest boy (1875–1959), appeared at the top of the stairs.

"Pa, you can stop yelling at God 'bout the flood. Grandpa's doin' it for us."

This hushed Thomas's words and all eyes went to Freddie.

"What are you saying, Freddie?" Thomas asked with trepidation.

"Grandpa is getting' God's and Noah's 'ttention. He's yelling 'bout some misery Holy Ones, and Lamb an' Tations an' Wicked Men. He's up on his roof."

A stunned moment of silence was followed by Thomas clicking into operation.

"Elizabeth, wrap this thumb up. William, Junior (Thomas Albert Jr. 1864 - 1956) save what you can of the tools. David, you're coming with me."

That's just what David John needed to round out the day. A climb up a slick roof to tackle a God-fearing and (to put it nicely) fragile-minded octogenarian.

David John gathered his wits; he needed to check on the remainder of The Family. With thunder blaring, rain pouring, and wind at his back he continued east on Princess Street and turned north into the flood on Chatham Street. His brother's home, Thomas Albert's (1839–1910), was three blocks up. Just as he turned off Princess Street a jet of water swept him off his feet and he slid almost ninety feet, as it were, home, the rest of the way to his brother's residence.

He made it up the porch but did not knock. He threw open the door and stood at the threshold for all to see; bloodied shirt, ripped trousers, collar hanging loose, blue neckerchief tied around his head, waistcoat and suspenders falling to his hips; he was a water-monster sight. Lightning struck and his terrifying condition was revealed. His sister-in-law, Elizabeth Evans Hersey (1842–1933), dropped the pail of rain water she was holding, spilling it onto the floor. The six older children froze in their tracks, gaping at him. The younger four, two sets of twins, started bawling.

It took five minutes to calm the twins and gather order.

"Great Heavens, David? What happened to you? Is everything alright in town?"

"Yes, yes, yes, everyone uphill is safe. I came to check on you, Thomas, and Father and Mother."

Clear to Elizabeth was the fact that it was David John who needed to be checked on and given care.

Repeated lightning strikes allowed him a look around the house. He gazed in amazement into the parlor. He was accustomed to Thomas's house being…untidy…perhaps chaotic. After all, there were ten children of all ages running amuck. But this sight was a calamity. Every carpentry tool used by his brother and their father was thrown, willy-nilly, about the room. The piano seemed to be housing the longer saws. Chairs were filled with hammers, compasses, and wrenches of every sort. Another lightning strike revealed a floor piled with miter boxes, clamps, axes, hatchets, every tool imaginable.

Elizabeth tried to explain. "The tool chests were too heavy to carry upstairs so they're bringing everything up one at a time."

This was an especially annoying turn of events. It had been David John, himself, who had carefully decluttered and systematized Thomas's and father's basement workshop. In David's opinion, the two of them had little sense of order. They had needed his expertise. Before David's intervention it had seemed to take the two an inordinate amount of searching through the hodgepodge to find a tool. There were two sets of most items. Decades before, while still a Yankee, father's Uncle Jonathan had purchased father's tools and arranged for his carpentry apprenticeship in Boston. Nostalgia, coupled with father's tendency to resent sharing, had caused some minor squabbles. In order to maintain peace father had solved the problem by graciously purchasing Thomas his own separate set of modern tools. A few of the tools were unique for Thomas, who was left-handed. It was necessary for there to be several sets of scissors. For the same reason, Thomas had made his own tape measures with all numbers and marks reading right-to-left. After David had finished, the basement was a well-ordered work shop; Thomas's tools hung on the north wall and most of father's on the east; every nail, screw, and bolt was sorted by type and size in labeled boxes. It had been an enormous and time consuming undertaking.

William Hersey, the oldest son (1863–1938), appeared up the steps balancing three boxes of nails. These he tossed on the settee and they immediately spilled onto the floor in a mixed mess.

"Is Thomas in the basement?"

A screaming torrent of explicitly non-Methodist language coming from below answered David's question.

"Thomas!!" Elizabeth yelled as they ran down the stairs. The un-Christian epithets became louder and coarser. Near the base of the stairs David gazed on the second scrambled scene of the residence. The floor was covered with three feet of rapid flowing water. An oil lamp sitting on a bench revealed the disaster. All small and loose items were washed up and clinging to the east wall. Most of the benched tools had been removed. Both doors had been broken open by the flood waters and the chairs and stools were hanging for life against the jams. Thomas stood by the south wall, cradling his right arm, bent over in pain. Blood was running heavily from his hand. The culprit, a large crosscut saw, lay underwater at his feet.

William hurried back down the stairs declaring, "Uncle, we are going to have a cave-in!" He was pointing at a small, two inch hole in the plaster of the north wall which was spewing a small fountain of water. The hole was clearly getting larger.

While Elizabeth flew into action to examine Thomas's hand (he was reticent to both let go of his arm and stop swearing) David scanned the premises for a solution to the growing hole.

"We have to stuff it with something," William yelled.

Rags? A hammer? A piece of wood (there was nothing small enough)? A hand-full of nails? His shirt?

Fast action was in need. The hole had grown to a triangular shape of about three inches and was getting larger. David, thinking "triangle, triangle" tore off his right boot and jammed it into the hole, toe first. It held. The Prussian blue mud stained silk stocking dangling over the boot heel made a colorful touch.

At this point Freddie, the youngest boy (1875–1959), appeared at the top of the stairs.

"Pa, you can stop yelling at God 'bout the flood. Grandpa's doin' it for us."

This hushed Thomas's words and all eyes went to Freddie.

"What are you saying, Freddie?" Thomas asked with trepidation.

"Grandpa is getting' God's and Noah's 'ttention. He's yelling 'bout some misery Holy Ones, and Lamb an' Tations an' Wicked Men. He's up on his roof."

A stunned moment of silence was followed by Thomas clicking into operation.

"Elizabeth, wrap this thumb up. William, Junior (Thomas Albert Jr. 1864 - 1956) save what you can of the tools. David, you're coming with me."

That's just what David John needed to round out the day. A climb up a slick roof to tackle a God-fearing and (to put it nicely) fragile-minded octogenarian.

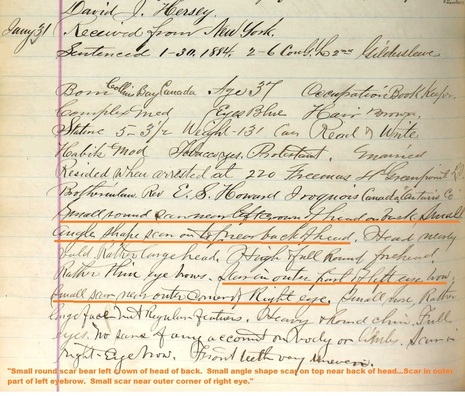

I must add a few notes. You should be able to tell that I am very fond and partial to my great, great, great uncle David John. This story is, of course, fiction. But the people, their dates, and occupations are accurate. There was a flood on Thomas Hersey's property in February 1878 as you can read in Ducks in a Millpond. The particulars of each person's personality are out of my imagination. However Thomas Albert and David John Hersey both had distinctive scars, as you can see below. The scars on David John's head seem unusual for a book-keeper. I am guessing that Thomas Albert was left handed because of his rather upright signature and his scar on his right thumb.

David John Hersey text above:

"Small round scar bear left crown of head of back. Small angle shape scar on top near back of head...Scar in outer part of left eyebrow. Small scar near outer corner of right eye."

"Small round scar bear left crown of head of back. Small angle shape scar on top near back of head...Scar in outer part of left eyebrow. Small scar near outer corner of right eye."

RSS Feed

RSS Feed