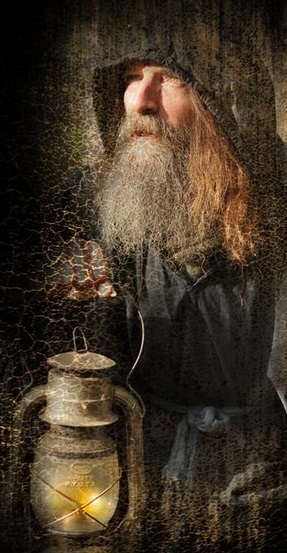

There are many peoples of interest that surface during an ancestor search. One individual that speaks loudly from the past is Doctor Samuel H Fee (about 1840- August 31, 1905). I found him in the 1881 census of Canada living close enough to the Hersey family to make his way into David John's Flood Run tale. It is likely that the Herseys knew the Fee family, by reputation if not personally. (Oddly, living in Kingston simultaneously is another Samuel Fee, a bookkeeper. Although David John most likely knew Sam Fee, the bookkeeper, he does not enter into our regard.)

Samuel and his parents, John and Mary Jane, along with two siblings, immigrated to Kingston, Ontario from Ireland during the Great Famine in 1847. There are many stories of hardship that accompanied this particular wave of immigration. Along with impoverishment, the stories include horrific Atlantic passages, sickness, isolation, and death. The Fee family, however, became a success story. John Fee became Kingston's Postmaster, marrying one of his daughters to the Assistant Postmaster. An older brother became a merchant. Another sister married a carpenter. The family was close and was still living together as young adults in the 1871 census. Seemingly well-to-do, the family also had one servant living with them.

Samuel attended medical school while living in Kingston: the Kingston hospital was an excellent training university. In 1862 Samuel endeavored to expand his medical experience in a novel fashion for an Irish-Canadian. He travelled south to Albany, New York, and volunteered as a surgeon in the United States Union Army. During the months of November and December, 1862 Samuel witnessed the terror and inhumanity of the American Civil War participating in the Battle of Fredericksburg, Virginia. It must have been a brutal experience.

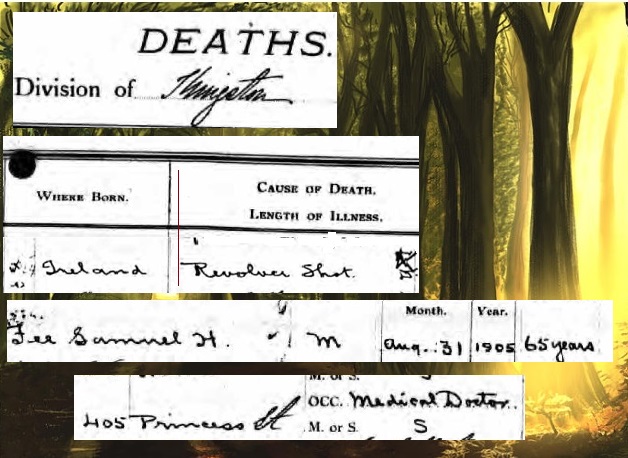

On a whim I wished to include a physician in David John's story and Samuel Fee was an easy inclusion. With the aim of obtaining more information on Fee I did some investigating. The first record I found for him was an August 31, 1905 death record.

Samuel and his parents, John and Mary Jane, along with two siblings, immigrated to Kingston, Ontario from Ireland during the Great Famine in 1847. There are many stories of hardship that accompanied this particular wave of immigration. Along with impoverishment, the stories include horrific Atlantic passages, sickness, isolation, and death. The Fee family, however, became a success story. John Fee became Kingston's Postmaster, marrying one of his daughters to the Assistant Postmaster. An older brother became a merchant. Another sister married a carpenter. The family was close and was still living together as young adults in the 1871 census. Seemingly well-to-do, the family also had one servant living with them.

Samuel attended medical school while living in Kingston: the Kingston hospital was an excellent training university. In 1862 Samuel endeavored to expand his medical experience in a novel fashion for an Irish-Canadian. He travelled south to Albany, New York, and volunteered as a surgeon in the United States Union Army. During the months of November and December, 1862 Samuel witnessed the terror and inhumanity of the American Civil War participating in the Battle of Fredericksburg, Virginia. It must have been a brutal experience.

On a whim I wished to include a physician in David John's story and Samuel Fee was an easy inclusion. With the aim of obtaining more information on Fee I did some investigating. The first record I found for him was an August 31, 1905 death record.

Revolver shot. An intriguing and alarming entry. Murder? I investigated further. Ultimately I discovered this obituary in the 1905 Journal of the American Medical Association:

Samuel Fee, a real man, suffering from depression in the summer of 1905, killed himself.

There is, of course, more than this to Sam Fee. He followed his father's path and became an important civil servant in Kingston. Civil War doctors often came away from the field with resolve, wanting to improve medical care. Fee was one of these individuals. He worked many years advocating better sanitation for the area, including the improvement of drains - the cause of the 1878 flood on Thomas Hersey's property. 1 2 3

For unknown reasons Samuel appears to have remained single; there is no record of a marriage and he is alone in each of the Canadian censuses in which he appears. He became depressed alone. He died alone. There are no descendants looking for Sam Fee, lauding his medical work.

There is, of course, more than this to Sam Fee. He followed his father's path and became an important civil servant in Kingston. Civil War doctors often came away from the field with resolve, wanting to improve medical care. Fee was one of these individuals. He worked many years advocating better sanitation for the area, including the improvement of drains - the cause of the 1878 flood on Thomas Hersey's property. 1 2 3

For unknown reasons Samuel appears to have remained single; there is no record of a marriage and he is alone in each of the Canadian censuses in which he appears. He became depressed alone. He died alone. There are no descendants looking for Sam Fee, lauding his medical work.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed